|

MICHAEL CHURCH

JULY, 2003

Thursday, noon, July 17: two airplanes departed John Wayne's 19L in formation. Nothing new, really: the airport hosts a disproportionate number of aerobatic planes, so formation departures and arrivals hardly merit a second look.

But this time, had you taken an extra moment, you would have seen something different. The wingman was standard--an Extra 300--but lead was unexpected: its high aspect ratio wings and bulbous fuselage gave the plane more the look of a glider than some muscular aerobat.

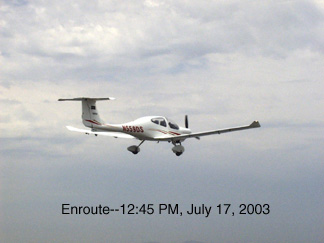

After a couple of minutes of picture taking, the two split apart—the chase plane returning to land, and the lead, now solo, continuing to the east. 17 hours later, holder of a new transcontinental speed record, DiamondStar 559DS landed at First Flight airport, Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

The record-making flight started with a proposal made by Laksen Sirimanne. A private pilot since 1992, he had discovered an open window of opportunity in the record book for the right airplane. The FAI (Federation Aeronautique International), the folks who monitor this stuff, recognize a transcontinental speed record for aircraft weighing 2205 pounds or less at the time of takeoff. The mark is not hotly contested, and Laksen had found that the current record holder was in there with an average speed of 52 mph. He figured the DiamondStar on the Sunrise rental line was the perfect plane to raise the bar: the right weight and a reliable cruise of 159 mph.

But rental would be expensive, and the entry fee alone was $1500. With a new baby to care for and normal financial tugs and pulls, 30 or 40 hours of rental fees were going to be too much. Could I help? Always generous, I promptly volunteered someone else: the aircraft owner might be interested in participating. Would Laksen like to meet him and discuss the prospects? He paused—this was a new entry into the equation—what would the second pilot be like? The record attempt was to be a major undertaking, and he was understandably cautious. But rental would be expensive, and the entry fee alone was $1500. With a new baby to care for and normal financial tugs and pulls, 30 or 40 hours of rental fees were going to be too much. Could I help? Always generous, I promptly volunteered someone else: the aircraft owner might be interested in participating. Would Laksen like to meet him and discuss the prospects? He paused—this was a new entry into the equation—what would the second pilot be like? The record attempt was to be a major undertaking, and he was understandably cautious.

Laksen, born in Sri Lanka, has several graduate degrees and is acknowledged to be very smart. He has climbed part-way up Mount Everest. He is also one of the nicest people I know, so his cautionary impulse may have lasted a full second:

"Sure," he said, and the meeting went forward.

On the other side of the table was Assaf Stoler, native of Israel, a computer software engineer, new dad, commercial pilot and Sunrise flight instructor in training. Also very smart. How could these two not get along? Both graduates of our school, both kind of other-world intelligent, both nice, both with three month-old daughters. It didn't take a degree in Kissinger diplomacy to set this one up.

Up for grabs: a speed record for a transcontinental flight in an airplane with takeoff weight not to exceed 2205 pounds. Official timing was to start with liftoff at John Wayne and end at Kitty Hawk. Every fuel and rest stop would count as part of the total elapsed time. This might explain the low speed of the previous record holders: they probably stopped to rest.

To qualify their airplane, Laksen and Assaf had first to sit in the DiamondStar as it was weighed. Fuel was added to bring the overall aircraft weight to the allowable limit, and papers were signed attesting to the maximum fuel permitted. From that point forward the pilots would use an accessory approved by the FAI to measure fuel at every fuel stop, then acquire a signature from an impartial witness attesting to the accuracy of the on-board quantity.

In addition to approving the fuel measuring device and writing the rules, the FAI provided documents for recording two critical events: departure and arrival. The first of these was faxed to the tower at John Wayne, where helpful controllers promised to faithfully record time off. The second went to Washington Center, in Leesburg, VA. First Flight airport is non-towered, so arrival time would be recorded by establishing radar identification directly over the destination field. A friendly gentleman at that facility's Watch Desk seemed well familiar with the procedure and promised to look after things personally.

The next issues revolved around choosing refueling points. There were four planned stops. The pilots planned conservatively, allowing well over 45 minutes fuel reserve at the end of each leg--provided the winds remained as forecast. The next issues revolved around choosing refueling points. There were four planned stops. The pilots planned conservatively, allowing well over 45 minutes fuel reserve at the end of each leg--provided the winds remained as forecast.

Departure was scheduled for noon Pacific time, Thursday, July 17. The initial leg would see the two well into the southwest US, with the first fuel stop planned for 3:30 Pacific time at St. John's, AZ. Then, as dusk fell they would pass Alberquerque and proceed just south of the Rockies. The second stop would be at 7:00 Pacific time in Amarillo, TX. After that, with terrain no longer a major factor, they would be flying through night skies.

The biggest challenge lay in choosing the next two airports. The plane required fuel—the rules required signatures, and Laksen and Assaf had to find fixed base operators (FBOs) with twenty-four hour staffing. I had warned them that even airports of considerable size might only offer self-fueling late at night, so out came charts and local Directory Assistance.

They chose Fort Smith, AR, for the third stop and were assured that live personnel would be on hand at their planned arrival time: 12 midnight, local. That left only one more challenge. Fortunately, at Sparta, TN, they found a kind airport operator who promised to await their arrival—ETA 4 AM local.

That seemed to do it. Baggage consisted of VFR and IFR charts, a light load of sandwiches and a couple of water bottles--and an alarm clock insisted on and supplied by me. FedEx would take care of delivering clothes for the return trip.

DEPARTURE-ENROUTE-ARRIVAL

Despite a somewhat last-minute approach to planning, everything seemed to be in place. Wives and babies came to the field for goodbyes, and the DiamondStar got airborne at 12:30--only a half hour behind schedule. As noted at the start, our Extra provided escort and camera ship duty for the first five miles. From that point forward the duo was on its own.

As told by Laksen and Assaf, the trip was almost picture perfect: they hit each fuel stop within ten minutes of ETA. On the ground, the team rivaled NASCAR pit stop efficiency: one supervised fueling, the other ran to the rest room. Then, the switch, as the first retired to rest and the second continued the pre-flight. You get the picture, I'm sure.

In the air, Assaf, the aircraft owner and the more experienced pilot, managed the mechanics of the engine and the GPS. Laksen's responsibility was pilotage: ensuring that reality outside the cockpit matched the virtual reality within and that emergency alternates remained in reach. Honeywell, through one of their autopilots, did most of the flying. Tropical storm Claudette, the cause of some pre-flight concern, was never a factor, and the weather remained clear for the entire trip.

At 7 AM Pacific, about an hour after the DiamondStar's earliest possible arrival time, I called Washington Center. I reached Mr. Llama, the same friendly guy I spoke with the day before.

"Oh yes--559DS checked in almost an hour ago."

Soon, a call from Assaf, by cell phone. They are there. FedEx isn't. Everything is perfect. They will await their clothes, then fly to an airport with a hotel. They don't know where, but everything is perfect. Moments later, a second call, from Laksen. Everything is perfect, thanks loads for the help. No he doesn't know what they will do next. Everything is, well, perfect.

Somehow, the pair avert terminal meltdown, get their clothes and fly to "RDU." Pressed, Assaf confirms the city is Raleigh, NC. That did it: I didn't hear from either again until 12:30 PM, their time, as they prepared for a leisurely departure and return flight the next day

Noon, Sunday. Revealing an unexpected hint of hot dog in one or both, the pair make a low pass at speed down the John Wayne runways before returning to land. Wives and babies are again on hand, with cake, champagne and a bushel of relatives and friends. Brought finally to earth, the pilots are exhilarated and proud, still on a high—but due to crash soon.

Before the excitement subsided, Laksen announced happily:

"You know Michael, you are one of the few people who didn't react to my proposal as if I was crazy."

Assaf's step-father was down-to-earth. Quietly he asked me, "In the grand scheme of things, what is the significance of this record?"

I told him what I thought. The record is smaller than many, but whether it lasts four months or four decades, one point will be the same: the flight was well planned and executed and will be a lasting accomplishment and source of pride for its two principals.

Away from the record books and wall plaques, the real value lies in recording the liberty these two pilots enjoyed to jump in a plane and fly coast to coast with such ease. With aviation under such heavy pressure in so many areas from our government and economy, it was refreshing to see its underlying promise of freedom so swiftly demonstrated.

|